by Eavan O'Dochartaigh

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

$99.99 (hardcover), Open Source (free)

Reviewed by Russell A. Potter

The importance of the role of visual culture in bringing imagery of the Arctic regions to a nineteenth-century public for whom these scenes represented an ethereal and almost unimaginable landscape would be hard to overestimate. That the exploration of this hitherto seldom-seen zone coincided with a wide variety of new and emerging visual technologies -- the woodcuts of illustrated newspapers, widely-reproduced prints and engravings, lithographs -- not to mention the panorama, the moving panorama, and (ultimately) photography -- makes them doubly exemplary, and among the first of what can truly be called "mass media."

And yet, there is another dimension to this development, one which encompasses the private, more ephemeral, visual materials actually produced in the Arctic by those who ventured there. A number of these, of course, were the basis of reproductions that were a key part of this mass audience -- but a greater number remained in private hands, gradually migrating to archival collections where many have lain unseen -- or at least unremarked -- for more than a century and a half. It is these visual works that Eavan O'Dochartaigh has brought to light in her remarkable new study, though she also discusses a number of public versions of these works.

O'Dochartaigh makes the case that these shipboard artistic productions be seen as "primary" documents, whether or not they later became the basis of reproductions. Looked at in this manner, they certainly present a different kind of visual vocabulary, in part due to the specific conditions in which they were produced. Shipboard sketches and landscapes were more often made in the summer, depicting a calmer and less foreboding environment than was standard in public productions. The winter output of these same amateur artists, rather than featuring icebound ships and bleak landscapes, tended to depict shipboard theatricals, humorous stories, and longed-for domestic scenes. She also observes that, when shipboard sketches or watercolors were converted into lithographs and prints, the printmakers drew from their own imaginations as they adapted often rough materials into polished products. While this certainly did occur in many instances, though, the degree of editorial "enhancement" must have varied -- when the shipboard artist was a skilled draughtsman, there was, in a sense, less for the lithographer to do. And, as she acknowledges, some of these reproductions, such as Burford's 1850 panorama "Summer and Winter Views of the Arctic Regions," were produced with the direct input of the original artists, the more solidly to seal the compact of authenticity between their "sketches made on the spot" and the finished painting. O'Dochartaigh's analysis of this panorama is extensive and detailed, and adds to our understanding of how its various elements drew from their source materials, as well as how the finished production and program sought amplify the sense of the natural sublime as well as the human plight.

Other chapters focus on the illustrated newspapers produced aboard several ships, particularly the Illustrated Arctic News (HMS Resolute) and the Queen's Illustrated Magazine and North Cornwall Gazette (HMS Pioneer and HMS Assistance). These periodicals, she notes, embodied quite a different, often humorous approach to the vagaries of shipboard life, both in their texts and in their illustrations. They also contained an element -- color -- which was not yet available in the illustrated papers of home. In the case of the Queen's Illustrated, most if not all of illustrations were the work of Walter William May, whose depictions of Arctic were later turned into an attractive set of lithographic views. Such views are analyzed in depth in the following chapter, with a sharp focus on the question of accuracy. With exact sources lacking for many of these lithographic plates, and the different capacities of a color lithograph over a charcoal sketch, it's a tricky business: are the sledge haulers having a harder time of it in the sketch or the stone? Some compositional adjustments are to be expected, as are additional details in faces and human figures. For while gifted with landscapes and ships, it seems that many of these shipboard sketchers weren't nearly as skilled with human figures, perhaps because they lacked artistic training. This was certainly not a problem at established lithographic firms such as Day & Son, whose array of artists with varied talents could handle any subject.

O'Dochartaigh's is an extraordinary study, particularly in its exploration of original artwork from archival sources that has, hitherto, been relatively neglected. We should also be especially grateful to Cambridge University Press for making the full book available as an Open Source text. I did have, as would anyone in a review of a book of this scope, some (mostly minor) quibbles: the reported faintness and infrequency of the aurora, for instance, is used to suggest that the panorama's highlighting of the phenomenon was exaggerated. For their infrequency, it's worth noting that the 1850's were progressing toward a solar minimum, while for the highlighting, the more proximate cause was Burford's earlier (1834) panorama of the Rosses' time in Boothia (which coincided with a solar maximum); its depiction of the aurora had been singled out for praise by the press -- surely the public would expect one again.

This points to what I would say is the book's one weakness -- by focusing on depictions of British searchers for Franklin, it misses some of the larger historical context, particularly earlier works which had already shaped the public perceptions of the Arctic and its explorers. It's also somewhat disheartening, as someone who has published extensively on the visual culture of the Arctic for the past twenty-odd years, to have the author inform me that the subject has been "largely overlooked," or that neither a fully art-historical or a committed interdisciplinary approach has previously been taken. And, though the present book's analysis of the 1850 panorama is certainly much more detailed, it's odd to have the nearly ten pages I devoted to it in Arctic Spectacles referred to as "brief." It's always, I suppose, part of the scaffolding of any new scholarly study to start by seeking a lack in what's been done before.

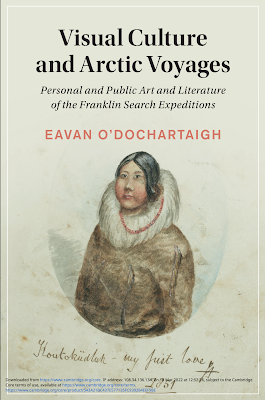

In that sense, the most innovative -- and most valuable -- contribution of this book is really to our understanding of the personal more than the public art of the various Franklin search expeditions. O'Dochartaigh has dug deep into the archival records, and brought forth not only many individual treasures, but fresh insights into the lives and practices of the shipboard artists of that time. The most powerful and touching of all these has, rightly, pride of place on the book's cover -- Edward Adams's "Koutoküdluk - My First Love" -- in it, we can see both the deep feeling and the fleeting fragility of a love long lost.

No comments:

Post a Comment