by Kenn Harper

Inhabit Media, 2022

Reviewed by Lawrence Millman

In far too many accounts of Arctic exploration, foreign outsiders reign supreme, while their Inuit guides and interpreters are followers, mere slaves helping their masters search for seemingly significant destinations. Released by the Inuit-owned publishing company Inhabit Media, Arctic historian Kenn Harper’s book series In Those Days blows the whistle on this prejudice. Inuit and Explorers, vol. 6 in the series, blows that whistle emphatically. In its pages, the Inuit are usually depicted as the true explorers, while the qallunaat (white folks) often seem like they’re stuck to sedan chairs. With respect to my own Arctic travels, I was never stuck to a sedan chair, but I probably wouldn’t be around to write this review were it not for my Inuit guides.

In Inuit and Explorers, Harper investigates unfamiliar Arctic stories. Here are two examples: R.C.M.P. Officer Joe Panikgakuttuk’s journey on the St. Roch as that vessel plies the Northwest Passage and 16th century explorer Christopher Hall’s jotting down of an Inuktitut word list. But Harper also offers new takes on more familiar stories, like Martin Frobisher’s 5 missing men, Samuel Hearne’s account of the Bloody Fall massacre, the ill-fated Karluk expedition, and the even more ill-fated Franklin expedition. As readers of Harper’s book Minik: The New York Eskimo will already know, all of his takes are impeccably researched.

I’m tempted to refer to the book’s essays as field work despite the fact that many of them describe incidents from several hundred years ago. That’s because Harper lived in the Arctic for nearly 50 years, first in Broughton Island (Qikiqtarjuaq), where he was called Ilisaijkutaaq (“the tall teacher”), and later in Iqaluit, Nunavut. Thus he’s much more intimate with the Inuit and their habitats than, say, a New Yorker staff writer might be. Likewise, he speaks Inuktitut, which means he can acquire information from Inuit elders about their history rather than, say, purloin not necessarily accurate information from the Internet.

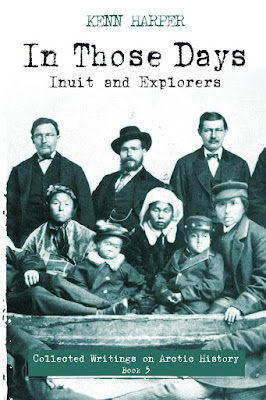

In addition to its 26 essays, Inuit and Explorers contains 40 pages of illustrations and photographs. There’s a delightful 1823 drawing of Inuit children dancing by the sadly neglected explorer George Francis Lyon as well as a sketch by Sir John Ross of the one-legged Inuk Tulluahiu, about whom Harper writes in “A Wooden Leg for Tulluahiu.” There’s a photograph of Iggiaraarjuk, an Inuk who told Knud Rasmussen about his father’s meeting with three grim-looking members of the Franklin expedition. There’s also a photograph, possibly taken by the author himself, of the elderly Uutaaq, a Greenland Inuk who accompanied Commodore Robert Peary (called “the great tormentor” by one of Harper’s informants) to the latter’s farthest North in 1909.

I have just one complaint about this book — its only references are to the issues of the Nunatsiaq News where the essays originally appeared. Harper offers a quite salient quote from archaeologist Susan Rowley about Martin Frobisher’s 5 missing men, but he doesn’t indicate where the quote comes from. There are other instances where I would have liked to see a citation, too. Otherwise, this is a masterful collection that I recommend not just to Arctic enthusiasts, but also to readers with only a passing interest in the Arctic, for it might turn that passing interest into a passion.